What We Learned from Research in 2025

I haven’t written many posts in 2025; here are the measly few I’ve managed to squeak out:

- Literacy Is Not Just for ELA: The Power of Content-Rich Teacher Tall

- More Productive Than an Hour of Instruction?: The Surprising Cognitive Science of a Walk in the Park

- AI, Mastery, and the Barbell of Cognitive Enhancement

While my bandwidth to peruse research has diminished this year (work has been busy, and I like spending time with my children) I have still encountered a fair number of compelling studies. In keeping with the tradition begun in 2023, and building on last year’s review, I am endeavoring to round up the research that has crossed my radar over the last 12 months.

This year presents a difficult juncture for research. Political aggression against academic institutions, the immigrants who power their PhD programs, and the federal contracts essential to their survival has disrupted research. Despite this, strong research continues to be published. Because research is a slow-moving endeavor, I suspect the full effects of these disruptions will manifest increasingly in future roundups; for now, the good work persists.

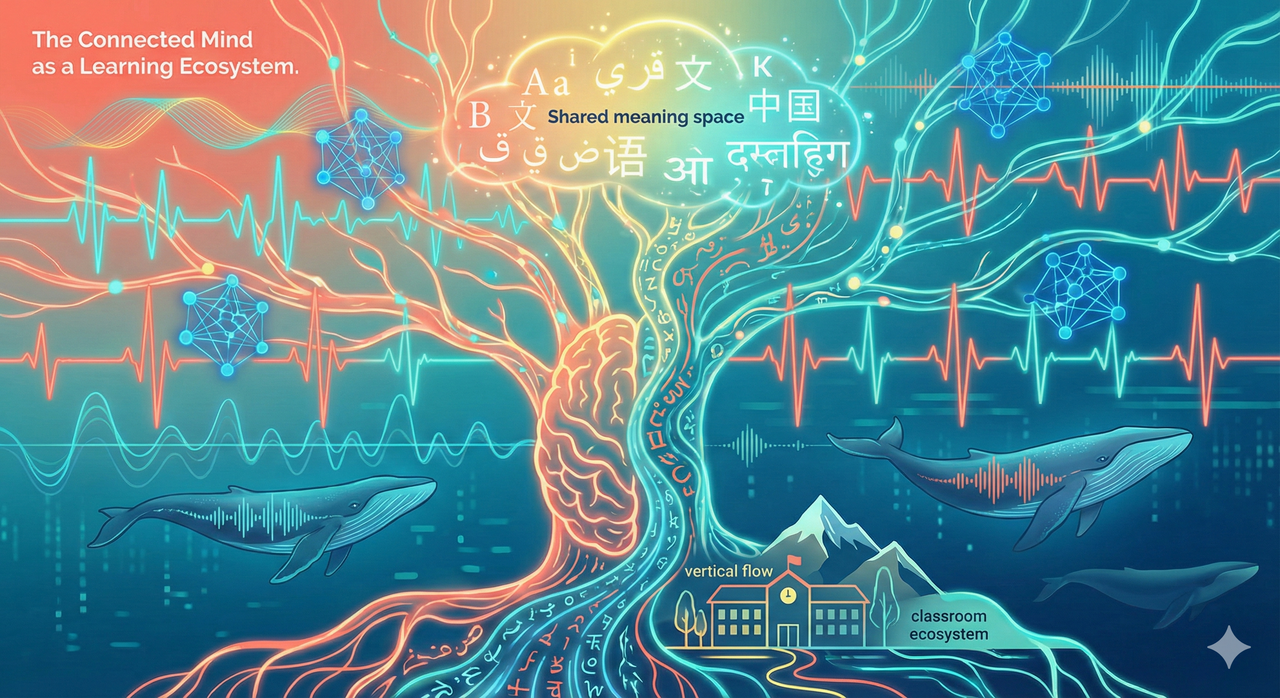

The research landscape of 2025 highlights a continued shift toward experience-dependent plasticity. This view treats the human mind as a dynamic ecosystem shaped by biological rhythms, cultural “software,” and technological catalysts. Learning is no longer seen as a linear accumulation of skills, but as a sophisticated orchestration of “statistical” internal models and external social and cultural and technological attunements.

Longtime readers will recognize this “ecosystem” view from my other blog on Schools as Ecosystems. It is validating to see the field increasingly adopting this ecological lens—viewing the learner not as an isolated machine, but as an organism deeply embedded in a biological and cultural context.

Our “big buckets” for this year have ended up mirroring the 2024 roundup, which means, methinks, that we have settled upon a perennial organizational structure:

- The Science of Reading and Writing

- Content Knowledge as an Anchor to Literacy

- Studies on Language Development

- Multilinguals and Multilingualism

- Rhythm, Attention, and Memory

- School, Social-Emotional, and Contextual Effects

- The Frontier of Artificial Intelligence and Neural Modeling

Let’s jump in!

This has been a great year for education research. I thought it could be fun to review some of what has come across my own limited radar over the course of 2023.

This has been a great year for education research. I thought it could be fun to review some of what has come across my own limited radar over the course of 2023.